Sea-levels will keep rising even with the Paris Agreement, latest findings show

- April 9, 2018

- Posted by: administrator

- Category: Environmental, Global

Latest findings from three recently published studies led by the University of Southampton show that with 1.5°C of warming, sea-levels will keep rising even with the Paris Agreement.

The studies are warning that the Paris Agreement, while aiming to hold global average temperatures to ‘well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C, does not take into account the longevity of sea-level rise (SLR).

While the commitment to SLR has been recognized in all Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, but the impact and adaptation implications have received less attention.

Furthermore, given the slow response of SLR to warming temperatures, the immediate differences in sea‐level and exposure at 1.5°C and 2.0°C is likely to be relatively small compared to their long‐term impacts if temperatures stabilize. However, this has never been quantified.

The new studies indicate that early climate change mitigation can reduce sea-level rise by approximately 0.40-0.50m by 2100 and 1.0-2.0m by 2300. This approximately halves the land area exposed by 2300 compared with a non-mitigation scenario.

Between 1.5% and 5.4% of the world’s population may be exposed to coastal flooding by 2300. Moreover, low-lying deltas are particularly vulnerable to the effects of sea-level rise.

To generate a range of scenarios of sea-level rise, the project team used an innovative climate modelling approach which reflected different magnitudes and rates of long term climate change.

The team found significant benefits of mitigating for climate change, particularly in the immediate future.

The lead author of the first study, Dr Philip Goodwin, lecturer in Ocean and Earth Science at the University of Southampton, found that climate change mitigation was very important in reducing sea-level rise in a centennial timescale.

The paper, published in Earth’s Future, is titled ‘Adjusting Mitigation Pathways to stabilize climate at 1.5 and 2.0 °C rise in global temperatures to year 2300’.

Dr Goodwin said:

“We compared the amount that sea-levels could rise by analysing mitigation scenarios for 1.5°C and 2.0°C. This indicated that by 2100, sea-levels could rise to 0.40m and 0.46m respectively, and by 2300, 1.00m and 1.26m. Compared with a non-mitigation scenario, mitigation reduced sea-level rise by 3.2m by 2300.”

Lead-author of the other two studies focussing on climate change is Dr Sally Brown, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Southampton.

“Around 100 million people are exposed to flooding today and this could double by 2100″

Dr Brown commented:

“Around 100 million people are exposed to flooding today and this could approximately double by 2100, and increase three fold by 2300, even taking account of climate change mitigation. Adaptation in coastal, and particularly delta areas, is challenging given the geographic scale, and continued efforts to reduce risk by governments and other national and international organisations is required.”

Many areas of the world are already sensitive to extreme water levels, such as delta regions, home to millions of people world-wide. An equivalent of a 1.5°C rise in sea-level will mean more extremes and is likely to lead to more wide spread and deeper flooding unless adaptation is undertaken.

The 10 countries most exposed are China, Russian Federation, United States of America, Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, Australia, India, Indonesia, and Mexico. A total of 7 out of 10 nations also have one of the tenth longest coastlines in the world (India, China, and Vietnam have shorter coastlines, but instead have numerous low‐lying deltas at risk from flooding).

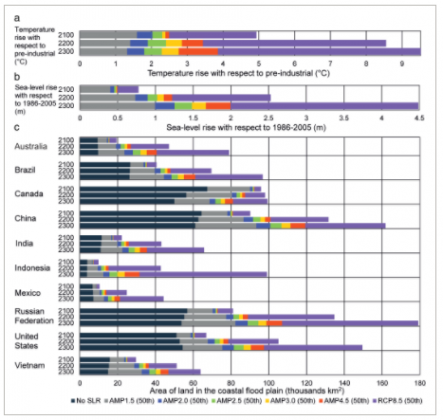

Figure illustrates that large areas of flood plain would be exposed even if sea‐levels were not rising.

(a) Temperature rise for each climate change scenario.

(a) Temperature rise for each climate change scenario.

(b) SLR for each climate change scenario.

(c) The top 10 country level exposure for the area in the 1 in 100 year coastal flood plain in 2100, 2200, and 2300 for each AMP and RCP8.5 (50th percentile).

The studies warn that the threat of long-term flooding does not stop even if temperatures are stabilised, threatening deltas world-wide.

Dr Ivan Haigh, co-author of the studies and Associate Professor in Coastal Oceanography at the University of Southampton, said:

“The implications of sea-level rise has important consequences for society for hundreds of years to come. Extreme water levels affect thousands of people around the world today, and this will increase with sea-level rise.

“These papers make an important contribution to determine who what or will be subject to long-term flood risk even under stringent climate change mitigation.”

Click here to ‘Adjusting Mitigation Pathways to stabilize climate at 1.5 and 2.0 °C rise in global temperatures to year 2300’, published in Earth’s Future

Click here to read ‘What are the implications of sea-level rise for a 1.5°C, 2°C and 3°C rise in global mean temperatures in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna and other vulnerable deltas?’ published in Regional Environmental Change

Click here to read ‘Quantifying land and people exposed to sea-level rise with no mitigation and 1.5 and 2.0 °C rise in global temperatures to year 2300’, published in Earth’s Future